How to Write a Great Instruction in PerfectIt

By Russell Harper

If your goal is to get everyone in your organization or group to follow your house style—and to learn the principles behind it—there’s more to it than simply adding terms and adjusting settings in the Style Sheet Editor. The exact words you use to describe the issue make a difference.

That’s where PerfectIt’s instructions come in. We’ve had some wonderful feedback from users telling us how much they like the instructions in The Chicago Manual of Style for PerfectIt. This article shows how you can provide that type of guidance for your colleagues.

What Is an Instruction in PerfectIt?

If you’ve used PerfectIt before, you probably know that when the program stops on a term to tell you that something might need fixing, it always includes a brief description of the problem, or what PerfectIt calls an instruction. You’ll see this in the pane to the left of your Word document under the name of the check.

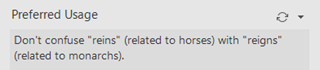

That’s a custom instruction tailored to a specific term. PerfectIt’s default instructions are usually less specific. For example, “A phrase appears with and without a hyphen,” or “A word is different from your preferred style.” Unless you override them, you’ll see these defaults even for terms you’ve added in the Style Sheet Editor.

Adding Your Own Terms

Let’s say you use the Style Sheet Editor to add a check for the word “inflammable” that suggests using “flammable” instead. It’s a common mistake: “inflammable” is a perfectly legitimate word, but because it could be mistaken to mean not flammable (with potentially disastrous results), “flammable”—which means exactly the same thing—is generally preferred instead.

Here’s what that check would look like when PerfectIt stops on “inflammable”:

Instructions That Do More

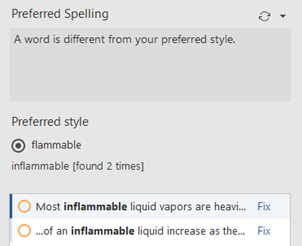

It’s easy to override PerfectIt’s default instructions. Simply enter your own text in the Instructions column. You can do this at any time, to new terms or to any of the existing ones. For example, for “inflammable,” you could go back into the Style Sheet Editor and add the following instruction:

“Flammable” is the standard term. Or did you mean “nonflammable”?

Here’s what that looks like in the Style Sheet Editor:

This instruction explains that “flammable” is preferred to “inflammable”—while anticipating the possibility that someone might have mistakenly used “inflammable” to mean not flammable.

The prefix “in-” does usually mean not (as in inedible, or not edible); the fact that the “in-” in “inflammable” literally means in (as in inflamed) catches many people off guard. Our instruction doesn’t explain all that, but it does teach the correct use of the word, in only 65 characters.

Accounting for Context

We’ve accounted in our instruction for the possibility that “flammable” may not be what the writer had in mind with “inflammable.” But there’s another consideration here: Sometimes “inflammable” would be preceded by the word “an” (as in “an inflammable liquid”). When that happens, clicking “Fix” won’t be enough (“an flammable liquid” isn’t correct).

You can account for this additional context by adding to your original instruction (as shown here in bold):

“Flammable” is the standard term. Or did you mean “nonflammable”? Note: You may need to change “an” to “a” (before “flammable”).

Users will now be reminded that there may be more to do beyond clicking Fix.

Teachable Moments

Early in the creation of The Chicago Manual of Style for PerfectIt, we recognized that the software could not be exhaustive in what it looks for. So we focussed on finding examples that teach the principles and enable users to find more issues themselves. You can do the same for your colleagues.

Let’s say your style sheet includes a couple of Preferred Spelling checks that look for “an UFO” and “a NBA,” respectively. You could add the following instructions:

(For UFO:) Use “a” before a word or abbreviation that begins with a consonant sound.

(For NBA:) Use “an” before a word or abbreviation that begins with a vowel sound.

Those instructions not only explain why PerfectIt is stopping, but they also state the principle behind the rule. And they would work for any “a/an” check. But you could make them even better by customizing them to include the term. For example,

Use “a” before a word or abbreviation that begins with a consonant sound. “UFO” is pronounced as a series of letters.

Use “an” before a word or abbreviation that begins with a vowel sound. “NBA” is pronounced as a series of letters.

Now users will be reminded not only of the principle but also why it applies in each specific case. There’s even room to explain how “UFO” and “NBA” would be pronounced, but that would be a bit more than most users would need.

Still, such a hint it might be helpful in some cases. For example, not everyone knows how to pronounce the acronym “EULA” (for “end user license agreement”), so you could add it in a check that looks for “an EULA” and suggests “a EULA” (as in “is a/an EULA legally binding?”):

Use “a” before a word or abbreviation that begins with a consonant sound. “EULA” is pronounced as a word (YOO-luh).

Now users should know exactly why the change is needed. They get a full explanation tailored to the specific term. And PerfectIt is not only catching potential errors but teaching the principles behind the rules.

Instructions Should be Short but Informative

PerfectIt’s instructions need to be short so that users can digest them quickly and keep moving through the checks. They also need to fit on the screen. But even so, they need to be just long enough to be informative.

Here are some basic guidelines.

Aim for no more than 140 characters, including spaces. If an instruction is a bit longer than 140 characters, test it in PerfectIt to make sure you can see the whole instruction, then edit it down as needed. But shorter is almost always better (100 characters is an even better target than 140). Users often ignore longer instructions.

Don’t be too prescriptive. Even the most clear-cut suggestion can be improved by accounting for context. For example, though “an EULA” is usually wrong, note that this sentence includes that very phrase—correctly, as an example of incorrect usage.

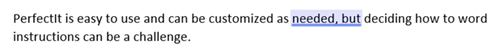

That doesn’t mean you can’t state a principle, as we’ve done for “a” and “an.” But avoid suggesting that something is simply wrong. Microsoft Word users understand what this feels like. For example, depending on your settings, Word’s grammar checker might flag “needed, but” in the following sentence:

Microsoft Word will tell you this: “It’s better to have no comma between these phrases.” But that’s not true in this case. Word’s grammar checker has missed the fact that there are two independent clauses in that sentence—and that the comma is therefore correct.

Like PerfectIt, Word makes it easy to ignore the advice, but it helps if the instructions you write hint at the possibility of the software being wrong. A simple “usually” can go a long way toward this end: “It’s usually better to have no comma between these phrases.”

Choose Your Words Carefully

Here are some tips for making sure your instructions are not only short and informative but also account for context and the fact that a check could be wrong in any given instance:

Use words that account for other possibilities, like “usually,” “may,” and “consider.” For example, in a plain-language check that looks for “prognosis” and suggests the more straightforward “outcome,” you could write this:

Instead of “prognosis,” consider using “outcome.”

Or in a check for the correct plural of “court-martial” (“courts martial”) you could use this:

The plural of “court-martial” is “courts-martial.” But “court-martials” may be correct as a verb.

Use words that acknowledge the user’s editorial judgment. This is especially important for checks that depend on context or that might entail something more complicated than replacing one term with another. Words like “if” can be helpful, as can a reminder to check the document carefully.

For example, in a check that suggests italics for “Spirit of St. Louis” (which may or may not refer to the famous plane):

If referring to the plane flown by Charles Lindbergh, “Spirit of St. Louis” is usually italicized.

And in a check that suggests using “decor” rather than “décor”—either of which is correct—you might write this instruction:

Check carefully. House style usually prefers the first-listed term in Merriam-Webster.

After all, “décor” might be correct in context, as in a verbatim quotation—not to mention the fact that the dictionary entry might change over time. For good measure, you could identify your house style—for example, with the name or abbreviation of your company.

Check carefully. ABC Inc. usually prefers the first-listed term in Merriam-Webster.

Embrace Repetition, and Customize as Needed

Though you might start to use the same instruction—or a close variation on it—over and over in the Style Sheet Editor as you enter new terms (or edit existing ones), don’t worry! Users will encounter them randomly as PerfectIt checks a document. And repetition like this can actually be helpful in teaching a set of principles and reinforcing a consistent editorial approach.

That doesn’t mean you can’t customize instructions to suit a particular term. As we saw with “EULA” and, especially, with “flammable,” some cases may benefit from a bit more explanation. And it can be reassuring to writers and editors to see that PerfectIt has accounted for specific cases.

PerfectIt is designed to give professional writers and editors the tools they need to do their work while teaching them the nuances of a particular style. If you write them carefully, PerfectIt’s instructions can help you take that to another level.

Russell Harper is the editor of The Chicago Manual of Style Online Q&A and the CMOS Shop Talk blog. Before helping PerfectIt’s team add “Chicago Style” to their proofreading software, Russell served as principal reviser for both the 16th and 17th editions of the Manual and contributed to the 8th and 9th editions of Kate L. Turabian’s A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations.